COVID-19 has exposed that, while the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) evangelists are preaching that we are experiencing a revolution, for many South Africans, 4IR remains a myth. The world’s new order of remote working and virtual learning has widened the digital divide and demonstrated that South Africa is far from fully embracing the 4IR. This blog provides insights on the potentiality of cultural knowledge systems, practices and processes as the foundation for building a holistic and inclusive digital transformation ecosystem in rural communities. The digital transformation journey of the Balobedu shows how one rural South African community, the Mamaila Tribal Authority (MTA), has been able to take meaningful and revolutionary steps to close the gap between digital policy and practice.

During virtual meetings and webinars, digital transformers and 4IR evangelists often complain about experiencing poor quality of service from mobile operators, the high cost of connectivity, and power outages. During such sessions, we hear about how the more privileged had to install fibre in their homes to improve their broadband quality and enable their children to participate in online learning. Sometimes we use such stories as ice-breakers to build rapport, laughing about our collective experience of poor internet. The reality, however, is that such laughs are tragic as they represent the severe inequality that remains a fact of life in South Africa. What kind of a revolution are we experiencing if 4IR champions, policymakers and researchers complain about poor connectivity and the high cost of data?

Mamaila Tribal Authority

Located 400 kilometers north of Pretoria, the residents of Mamaila Tribal Authority (MTA) – like many other villages in South Africa – do not have access to reliable and affordable internet. In Limpopo province, only 1.5% of the population have internet access at home (Statistics South Africa, 2020). In MTA, however, nearly 50% of the population has internet access. The digital transformation journey in Mamaila village includes the deployment of the Mamaila Community Network, connecting 6 villages, the construction of a Community Computer Solar Lab, mentoring and training of youth in digital skills and the development of a Cultural preservation website known as Our Heritage. This community exemplifies new narratives on rural digital transformation while providing practical steps on how to close the gap between policy and practice.

Mandhwane, Mind Mobilisation, and Digital Mandhwane

Drawing on the lessons from Tshepo Khumbane’s philosophy of Mantlwantlwane (learning by doing) and Mind Mobilisation methodology, the community of Mamaila is on a digital transformation journey.

Pronounced and spelled differently across Southern Africa – Mantlwane (Northern Sotho/Tswana) Mand(h)wane (Khelobedu)/Mahundwane (Tshivenda), Mahumbwe (Shona) – Mandhwane is a skills and knowledge transfer system that is practiced by many Southern African communities. Mandhwane prepares children to become capable members of society. During Mandhwane, children imitate adult roles, mimicking ordinary life and receiving feedback from their parents. Some of the principles of Mandhwane are;

- Learning by doing

- Trial and error

- Continuous improvement (failure and mistakes are part of learning)

- Role modelling, peer learning, and support

- Frugal innovation (work with what you have)

- Storytelling

- Co-creation and

- Systems thinking

Mind Mobilisation as a social learning and reflective process grounded on the values of Ubuntu/Botho. Khumbane designed Mind Mobilisation to inspire communities to apply integrated and indigenous methods to manage their water resources and food security. Mind Mobilisation has helped communities to actively take control of their education, assets, services, and development without being reliant on external aid and government (de Lange, Kruger and Stimie, 2009)

A Digital Mandhwane approach aims to facilitate the creation of culturally embedded digital economies while enabling communities to leverage digital technologies to support their aspirations and day-to-day practices. Digital Mandhwane suggests that a holistic and inclusive digital transformation must be people-centered and supported by leadership that is capable of:

- creating an environment that enables access and ownership of appropriate digital infrastructure;

- facilitating the development of digital skills to ensure inclusive digital adoption and localisation of digital services.

The Digital Transformation of Leola

When South Africa entered the first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, residents of Mamaila did not have any means to perform their communal processes such as Aretsebaneng (family gatherings), Leola (communal funeral scheme), and Kgoro (tribal court), which depended on social interactions and oral communication. One of the most affected processes was Leola. Leola is a traditional crowd-funding and sourcing process that promotes social cohesion in the community by offering financial relief and human resources to bereaved families. For a very long time during the lockdown, the residents could not gather in groups to discuss their Leola contributions or offer condolences to grieving families.

The residents of Mamaila felt the severity of the digital divide when the country went into COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. Unlike the 4IR evangelists and some urban dwellers with access to the Internet and free Wi-Fi, the residents of MTA could not rely on digital technologies to support their communal processes. The unavailability of localized digital solutions, the high cost of data bundles, lack of digital skills, and unreliable connectivity infrastructure, coupled with the COVID-19 social gathering restrictions, created uncertainty on the future of Leola. Those responsible for Leola wondered if COVID-19 meant the end of a practice that promoted social cohesion in the community for many decades. The residents of MTA were hopeful that one day they would be able to use technology to manage their Leola process. The community hoped that digitizing Leola might contribute to promoting transparency and accountability as well as allowing those who have moved away from the village for work to be able to participate. According to van Stam (2021), digital technologies are inherently linked to a colonialising power and, in general, unaligned with local, African ways of knowing. Clearly, the digitization of Leola required a different approach from the information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) strategy, which often imposes digital solutions into communities and excludes the local ontologies and epistemologies in the process. Guided by the principles of Mandhwane, the community of Mamaila embarked on a digital transformation journey grounded in their cultural framework of Ubuntu (collectivism and relational).

A Holistic Approach to Digital Transformation

Given this unique circumstance, I have been conducting action-based research on the Digital Mandhwane implemented in Mamaila. My aim is to investigate how cultural knowledge systems could facilitate the active and inclusive participation of African rural communities in the digital era. Digital Mandhwane is informed by local cultural frameworks (ways of being, doing, and knowing), identified through a cultural awareness of the practices and digital patterns at household level.

My action research was co-designed with the community through focus groups and workshops, including the incorporation of recommendations by digital transformation and cultural & heritage experts that I interviewed. I also conducted household surveys on the digital patterns of those in the community and how those changed over time. The research findings revealed that the cultural framework of Mamaila is made of deeply embedded knowledge systems, practices, and processes transferred from one generation to another, rooted in the values of Letjema/Letsema (collective work) and Motho ke motho ka batho/Ubuntu (I am because you are). Letjema is a cooperative system that brought people together for work activities such as farming. In today’s language, Letjema could be understood as crowdsourcing.

Photo by Kgopotso Ditshego Magoro

In the context of Mamaila village, Digital Mandhwane led to the development of several digital solutions for the community:

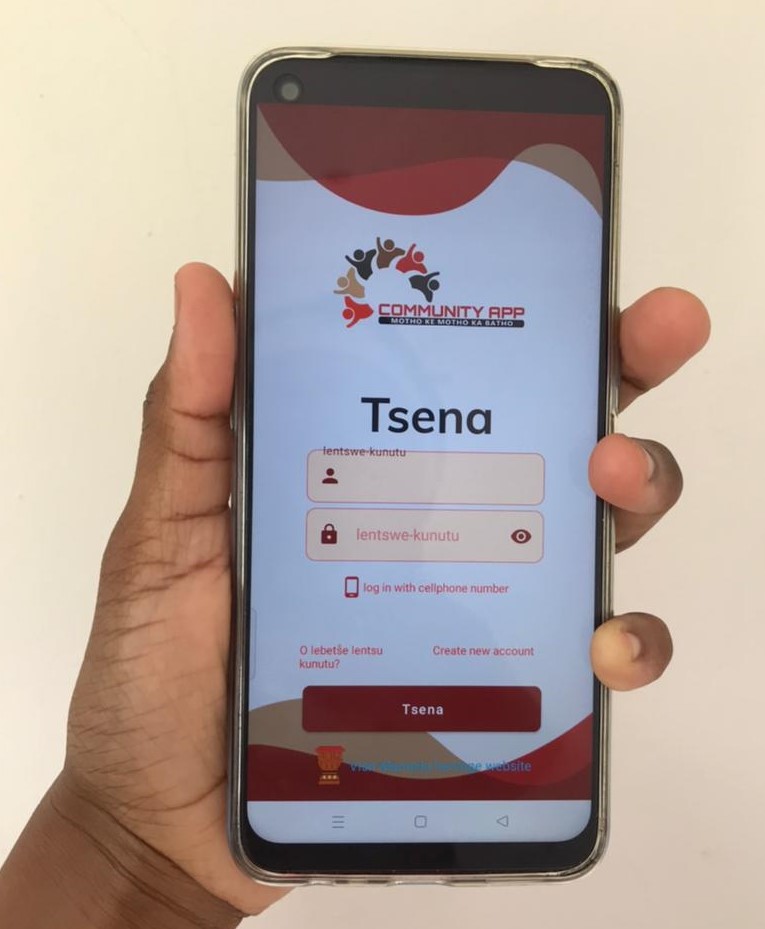

- App known as Motho ke Motho ka Batho (I am because we are),

- the Mamaila Community Network, connecting 6 villages,

- a Community Computer Solar Lab

- a cultural preservation website known as Our Heritage.

The Motho ka Batho App aims to support the community in managing the Leola process with record-keeping, asset management, communications, and information sharing. It also promotes neighbourhood safety by enabling residents to report incidents. The Mandhwane approach applied in the development of the App created a learning and knowledge exchange environment that enabled the community to reimagine their digital futures and to identify digital opportunities within the context of their collective cultural framework. During the co-creation process, the various Maola structures within Mamaila defined their Leola processes and identified areas that could benefit from digitization. More than 12 months later the App continues to go through enhancements to incorporate user requirements and feedback. The App has become an important part of Mamaila’s digital transformation agenda by creating awareness of how other community processes such as livestock and graveyard management could benefit from digitization.

Digital Mandhwane: African philosophy of learning by doing

Although the Digital Mandhwane is still at its infancy stage and the Community App is not fully rolled out in the community, the progress made in Mamaila provides insights on how the consideration of cultural knowledge systems, practices and processes might contribute to the creation of holistic and inclusive digital transformation in rural South Africa. The inter-generational conversations and digitalisation of the communal processes guided by local knowledge systems exposed both the young and old to digital opportunities and the role of heritage in facilitating localized innovation. Digital Mandhwane environment demonstrates that a culturally embedded approach could lead to the emergence of rural-based digital innovators who might lead the fifth Industrial Revolution (5IR) and many other revolutions to come and develop digital products to help them manage humanitarian crises such as COVID-19 and other pandemics.

Acknowledgements

Digital Mandhwane is implemented as an academic action-research with the support of the National Treasury and MICTSETA. I would like to thank the Mamaila Royal Council and the community of Mamaila for their support, the Internet Society, Computer Aid International, Zuri Foundation, Kichose Technology, and the LINK Centre. I would also like to thank Dr. Luci Abrahams, Mr. Pardon Mabunda, and Mr. Oscar Mokgola for enabling the various components of this research with their resources.